Consequences of incorrect treatment

With reference to the article under Foreign doctors: language problems and misdiagnoses by DocCheck, which points out the serious consequences of treatment by poorly trained or untrained foreign doctors, I can confirm this painfully and repeatedly with the following story.

All this only happened because the Federal Ministry of Health of Karl Lauterbach has this health system that is turned away from the people, who himself, like all the politicians and civil servants who are paid by us people from Kassel to finance their carefree dolce vita, only receives the best treatment from qualified doctors trained here.

For us people from Kassel – the derogatory term used by doctors for SHI patients, i.e. the tax and contribution-paying “subhumans” in this country who can no longer afford this due to the lousy treatments – there are almost only the most unqualified dottores, apart from exceptions that are no longer worth mentioning because there are too few of them.

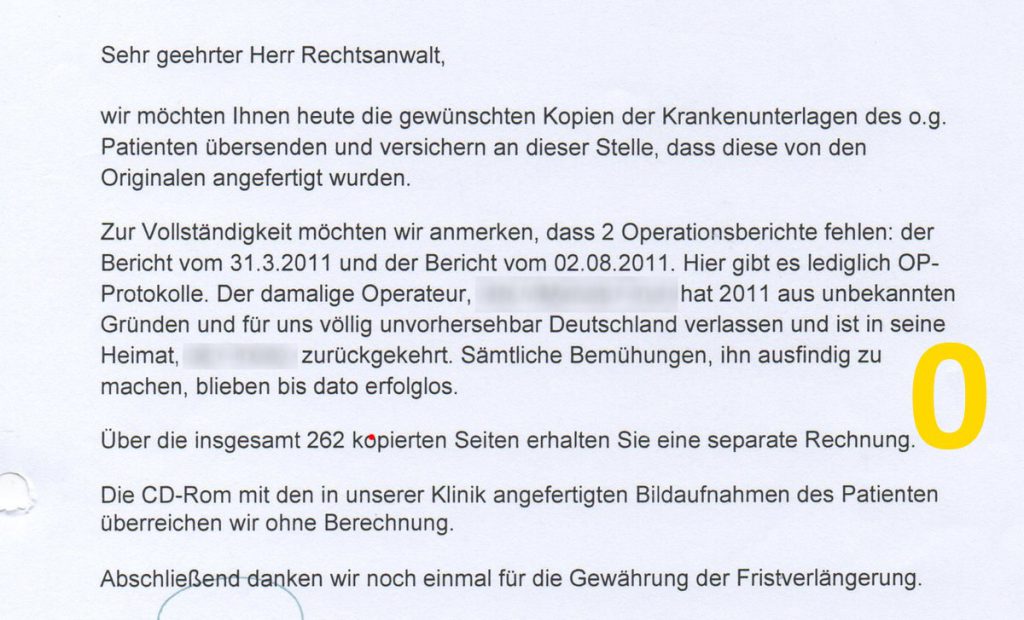

My story with life-threatening consequences, which is currently coming to a head again, ends with the fact that the doctor who provided the wrong treatment? has disappeared abroad unknown (picture 0).

Here we go:

Well, here is a true story that has become topical again, and it doesn’t matter whether you are alone or not, because with meningo(myelo)encephalitis developing again in the unknown near future, it will be difficult or even impossible to find contact points even in an emergency:

Unfortunately, I keep forgetting what it was like in 2011, when I had absolutely identical symptoms that only led to bacterial meningoencephalitis a few months later.

I would like to go on to describe how this matter came about and the difficulties that repeatedly arose, which led to the “I have to go” reflex in doctors.

In 2010, on the recommendation of a neurosurgeon in my home town, I was referred to Clinic A, where neuropsychological tests, among other things, were carried out over a long period of time.

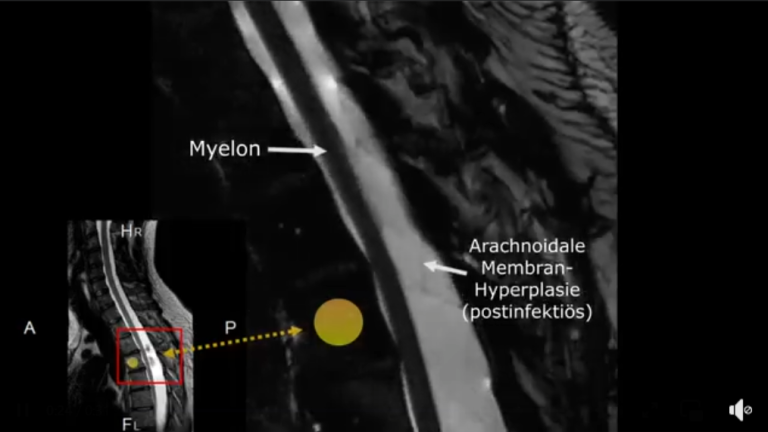

A VP shunt was then implanted in January 2011, and this led to a more than significant improvement in several areas, which was a kind of continuation of the adhesiolysis in 2009, to extensive intradural adhesions of almost the entire thoracic spine, which at that time blocked the CSF and compressed the myelon.

I have an unknown, congenital dysmorphia syndrome, which would have caused me more and more problems since my childhood with many health problems to be suppressed, ignored by all doctors without exception throughout my life, except for a gentle hint from the University of Leipzig, if I had not literally switched off my body.

Okay, in any case, the joy of the VP shunt had already evaporated during the follow-up rehabilitation when I started experiencing these intermittent, shorter or longer-lasting, point-like, stabbing, pulling pains in my abdomen, just like the ones I have now.

I then went to Clinic A several times to have everything checked, including serum, and the cerebrospinal fluid was checked by puncturing the valve, without any pathological results.

From mid-2011, everything picked up speed, which led to a total of eleven surgical interventions that year.

The “tickling” of the distal catheter on the appendix led to acute appendicitis, which initially went unrecognised, and subsequently to local peritonitis.

Only then was an appendectomy performed at home, but the peritonitis was inadequately treated and the catheter was supposed to have been moved to the left side.

After that I was even worse, I was transported (deported) from the surgical department to clinic A after an abscess was supposedly seen in the bowel.

A revision there in Clinic A of the Visceral Surgery Department, accompanied by neurosurgeons, revealed that the catheter was still in the “pathogen swamp” on the right.

And there was no abscess in the bowel either, so the surgeon at a large clinic in my home town had lied through his teeth.

As soon as I was back home after the rehabilitation and selective recovery, I felt so bad a few days later that I was almost out of it and I can’t remember a few days.

After an emergency admission to Clinic A, the dilemma of meningoencephalitis was realised, the germs, gram-positive cocci, had finally made it to the top.

The entire VP shunt was removed and reimplanted later.

The inflammatory cerebrospinal fluid was collected externally via an external ventricular drain (Fig. 5) and then very successfully administered intrathecally with vancomycin so that the intensive care stay could be ended after just three days.

Unfortunately, there were further problems afterwards; in fast motion, I probably experienced almost all, or even all possible shunt complications, including a slit ventricle syndrome.

However, this was not the most drastic event, as this would only occur in 2013 and 2014 and would lead to the lasting effects of the situation we have today.

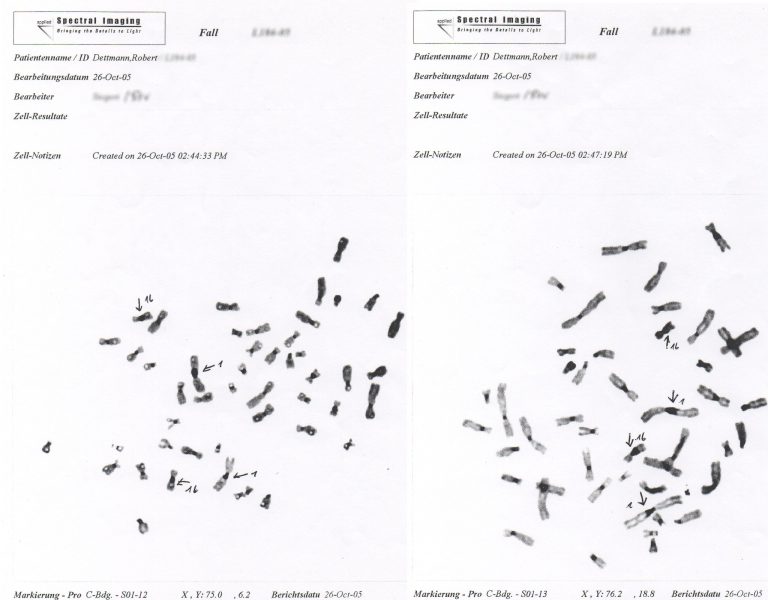

So in 2013, after years away from my place of work in M, I was due to go on another professional trip to Romania, where we have a partner company in the field of software development.

The flight to Cluj-Napoca and the stay at the destination initially went without a hitch.

On the third day, however, I was suddenly barely able to walk and fell asleep at my desk in the office.

So I shortened my stay and flew back to M, then took the train from there to my home town.

One day later, I had such severe back pain, again in the thoracic spine area, that I had previously described it as toothache in my back before the adhesiolysis.

So I contacted Clinic B, the treatment centre for this, as I was also involved in a research project on new spinal imaging diagnostics that was being developed there together with a university.

I went there at the end of 2013 and it was already apparent that there was a large accumulation of cerebrospinal fluid in the lower thoracic spine.

So an inpatient appointment was arranged at the beginning of January 2014, which meant that from then on they were supposed to take over something that they had never intended to do.

The extent of the problem only became apparent when the entire shunt was checked.

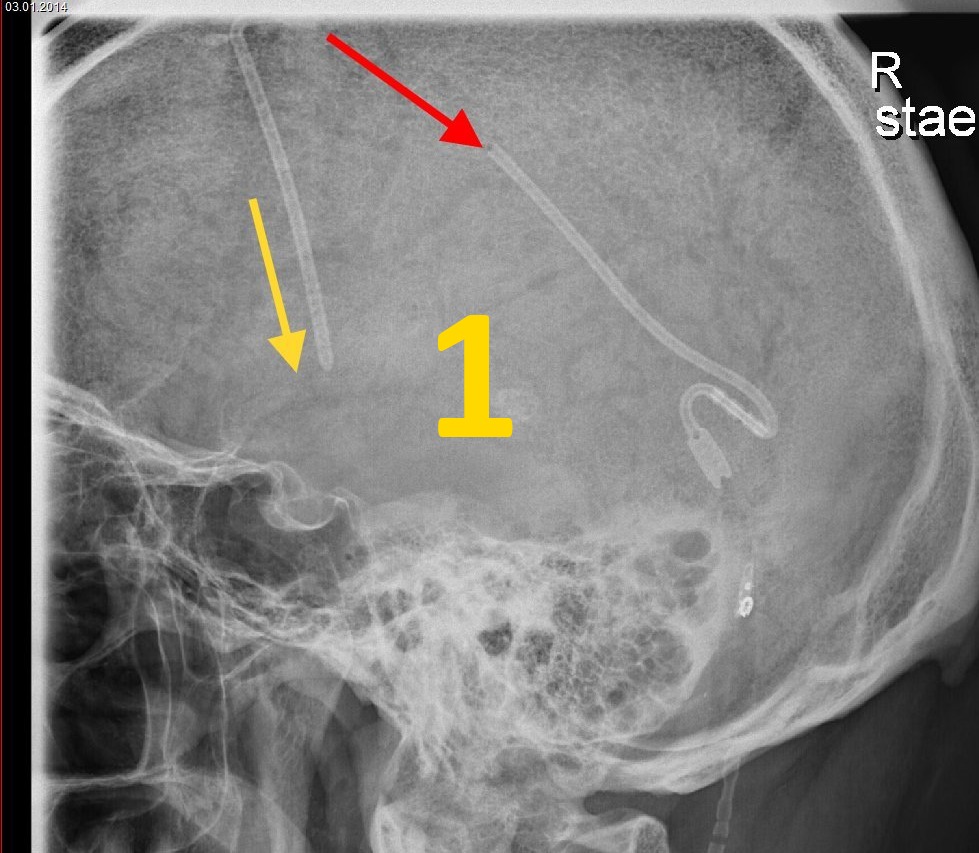

The shunt was torn off intra- and extracranially (image 1), the valve was somewhere down the side, I didn’t even notice it, the lateral x-rays look funny.

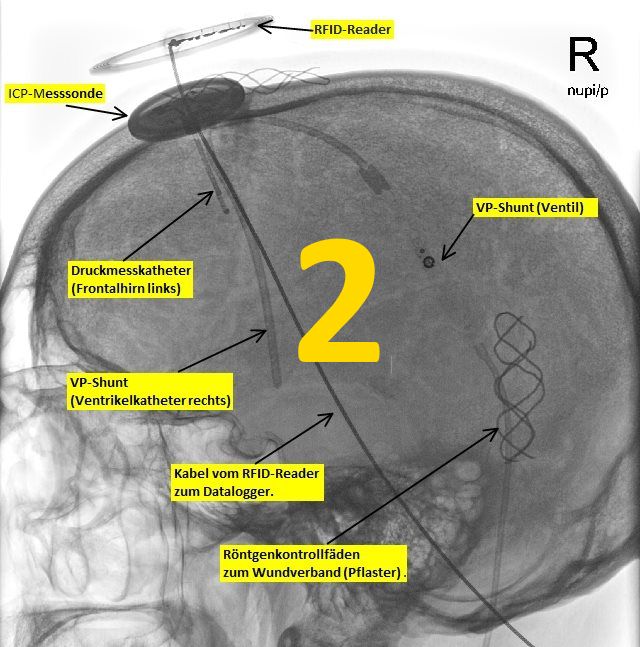

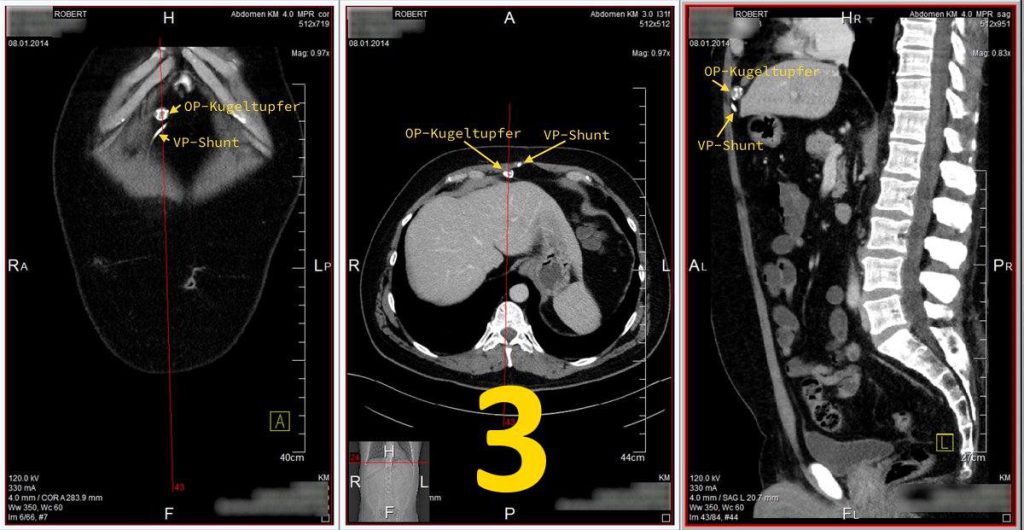

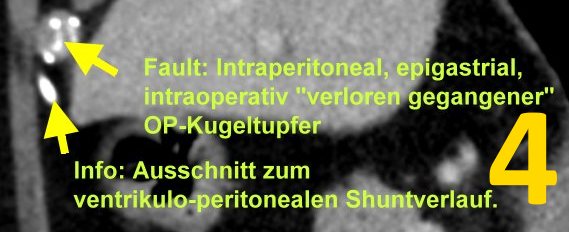

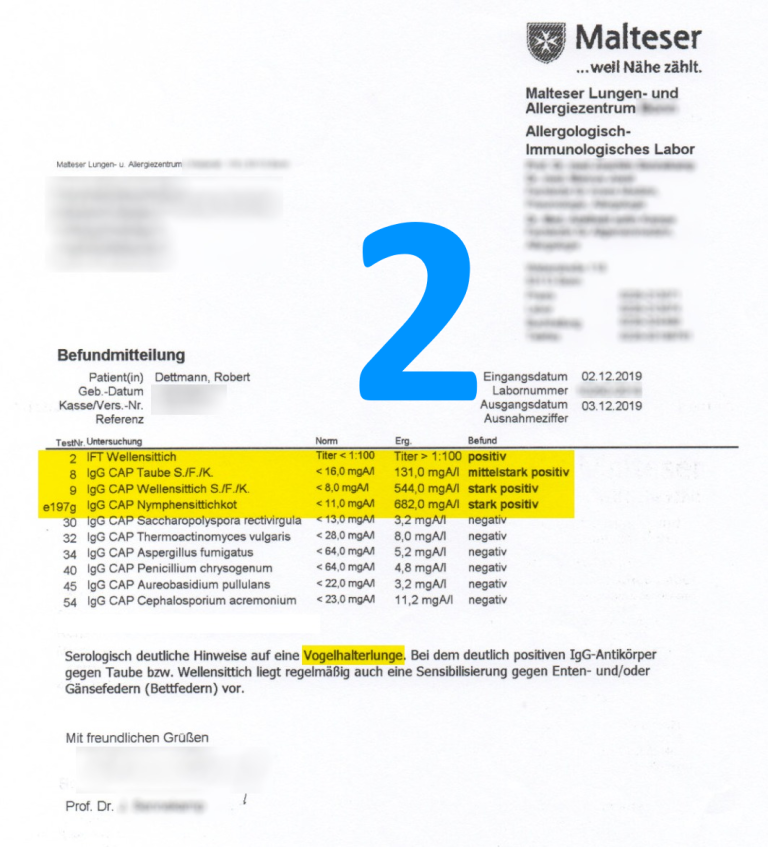

Before this was corrected (image 2), I was asked to have an abdominal CT scan because something else was seen (images 3 and 4).

And that was a spherical swab that had been left lying intraperitoneally epigastrially in clinic A during the revision after the infection.

Clinic B did not want to remove it after all, probably for insurance reasons.

The swab was removed by the neurosurgery department at Clinic C in 2015.

Before leaving for Romania, I had the shunt checked there and it was found to be normal.

However, it was later discovered that the torn shunt had already been clearly visible on the CCT overview image, meaning that I had been walking around with it for some time, which explained the many problems, one of which was spasticity with dislocation and a torn medial ligament.

In any case, after a later, non-binding enquiry from me about the problems I was now having with the fact that nobody wanted to resect, the neurosurgeon in charge was able to convince his boss to do it.

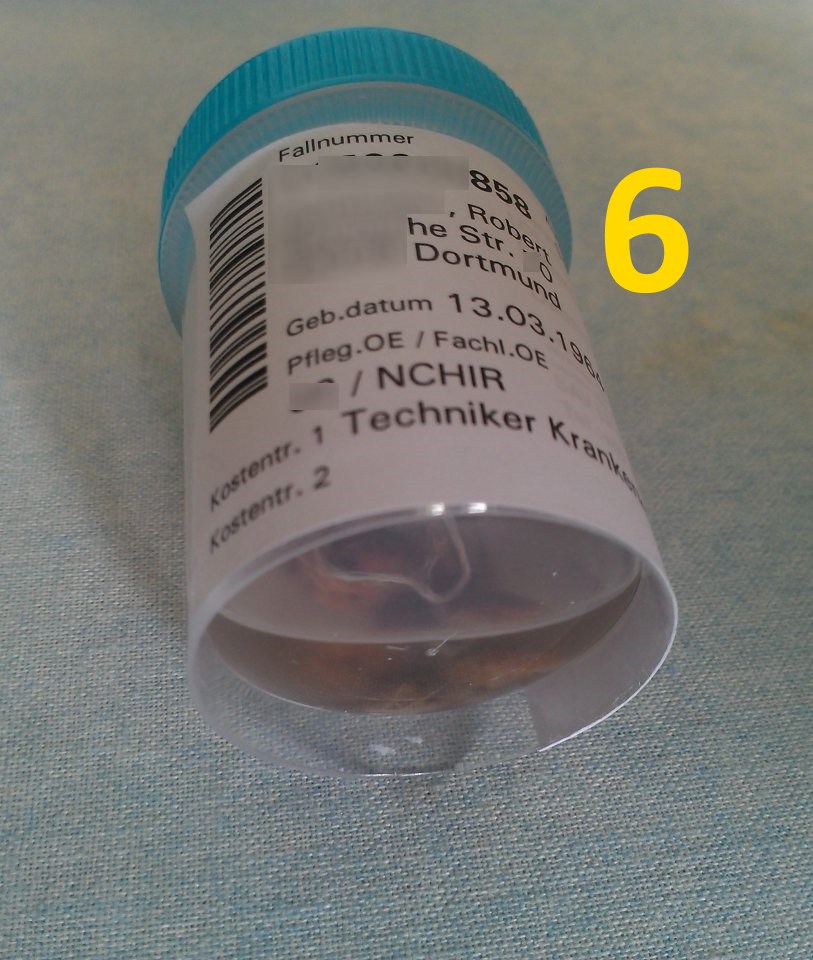

The procedure was completely unproblematic, the swab was already dissolving but could still be completely removed and then floated in an evidence container with formaldehyde (Figures 6 and 7).

However, what was found in Clinic B makes everything much more complicated.

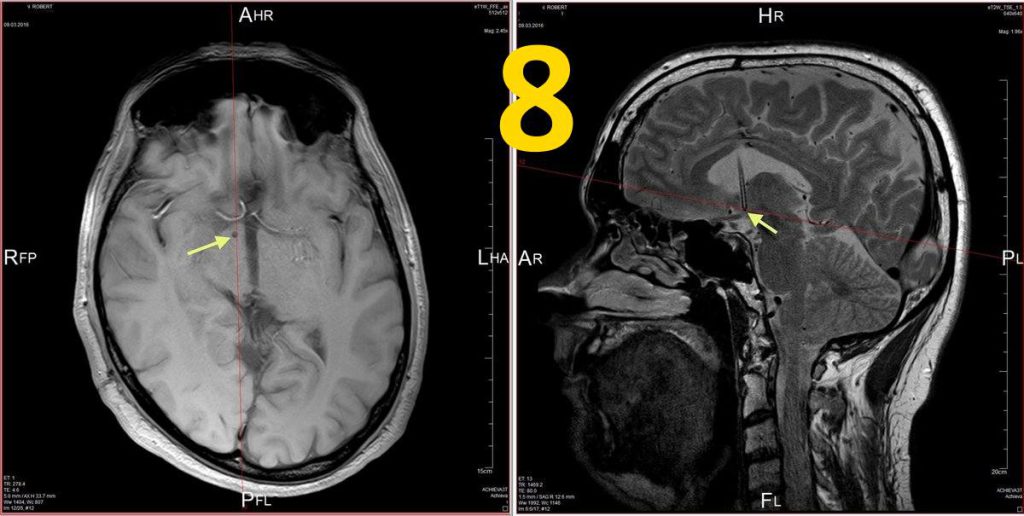

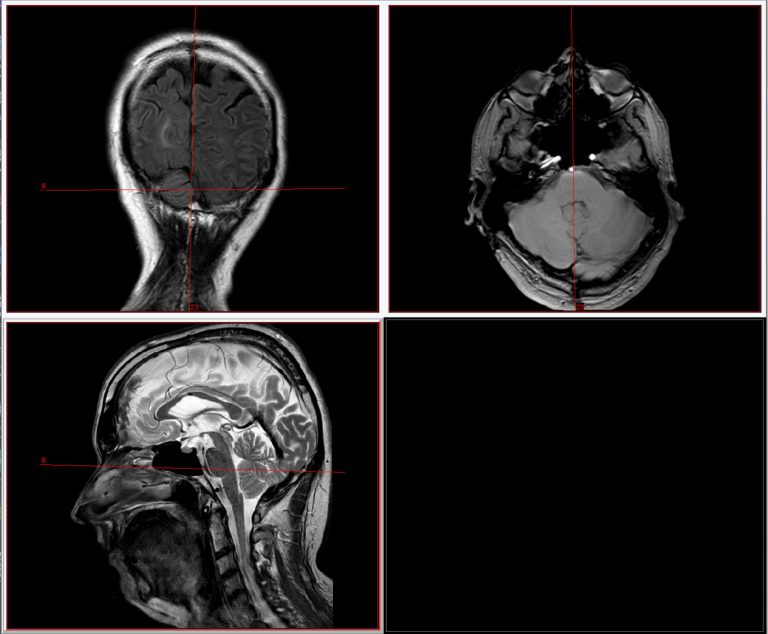

At some point during the revisions in hospital A, the ventricular catheter must have broken through the floor of the right lateral ventricle, leaving the tip of the catheter in the brain parenchyma of the hippocampus or hypothalamus region (Fig. 8).

At some point, a haemorrhage also formed around the intracerebral shunt, probably unnoticed, with subsequent development of gliosis.

This means, however, that a renewed shunt infection could be very complicated and, in any case, could pose a latent vital threat, something I had to fully realise years ago.

I guess that, with my full understanding, this will also be the reason why nobody really wants to do anything with my case.

However, clinic A, understandably, can no longer be a possible place of treatment.

Incidentally, the neurosurgeon who treated me at the time is unknown and has disappeared abroad (Figure 0).

Well, he may not have had sufficient training, if at all, a recent public issue concerning the training situation of foreign doctors working here, so the checks may be too lax …